Dr. Herman Pontzer, the leading scientist that formalized the constrained energy expenditure model has published a very good book on metabolism called Burn: The Misunderstood Science of Metabolism (India, USA). If you like this series, I recommend picking up a copy.

In the previous two parts of this series, I talked about metabolism and its components, and energy production in the body. In this one, I’m going to talk about energy expenditure in the body.

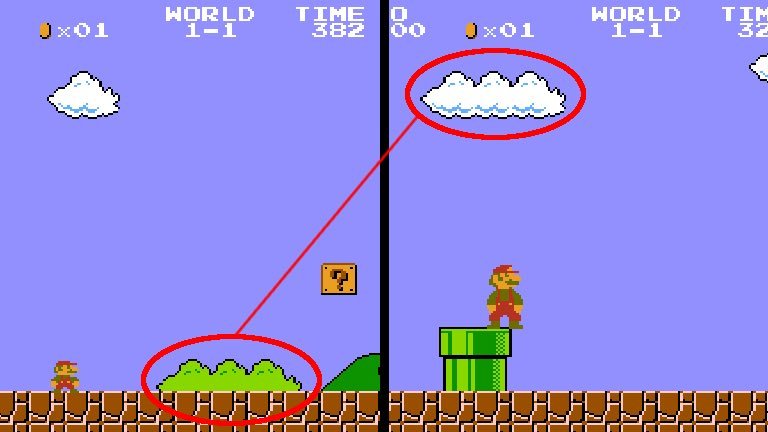

The Additive Energy Expenditure Model

For the longest time, this is how people thought the human body worked:

- You have a base energy expenditure that you need to stay alive (labelled as “other” in the chart above)

- Activity costs energy, and the more activity you do, the more total energy you burn (labelled as “PA” in the chart above)

This is the additive energy expenditure model. Simple to understand and “obvious” to many people.

The Problems With The Additive Energy Expenditure Model

The most obvious problem with this model as observed by every decent athlete and coach (and even just guys trying to lose weight) was that it didn’t seem to work. Or at least that it was incomplete.

What that means is that everyone noticed that if you keep eating the same amount of food, and add some exercise to create a caloric deficit, you would initially lose as much weight as expected, but then over a few weeks/months, you will lose less and less weight than this model will have you predict.

And this is AFTER accounting for changes in body weight and composition.

The model didn’t seem to “hold good”.

To put it in different terms, if you had a 500 calorie deficit coming from added exercise (and added more exercise to account for your weight decreasing over time to maintain the calculated deficit at 500), you would keep losing less and less weight than you would at a true 500 calorie deficit.

Moreover, every athlete also noticed that adding a ton of exercise destroyed them psychologically and physically despite eating more food to compensate for their exercise energy expenditure.

They had no libido, irritable mood, constant feelings of fatigue and exhaustion, and all other signs of overreaching/overtraining. If they kept overdoing it, they would eventually fall sick.

So clearly the additive energy expenditure model wasn’t telling us the whole truth.

The working theories that coaches and athletes had were:

- When you add more exercise to burn calories, you move around less when you aren’t exercising (e.g. you walk less, you fidget less, you sit and lie around more, etc.) so you “save up” some calories in the rest of your day

- There is some element of your metabolism going down when you are in a prolonged caloric deficit. The working term for this used to be “metabolic damage” because it was thought to be a bad thing (we now know this as metabolic adaptation and is thought to be a good thing)

- Some coaches (at least in the eastern half of the world) thought that training hard used “sexual energy” and this is why athletes who trained a lot had no libido. They would tell their athletes to not have sex for a week or two before competition.

But no one was certain what was actually going on. There was no formalized model that accounted for these things.

The (Surprising) New Research

In the last few decades, a highly accurate way of measuring total energy expenditure using doubly labelled water became possible to use at scale.

It’s been around since the 1950s but used to be absurdly expensive (entirely cost prohibitive for use with humans) but over time isotope prices have dropped significantly and it is now the gold standard way to measure total energy expenditure in humans.

It is not just highly accurate but also works under normal living conditions (you don’t need to live in a lab). I won’t get into how it works because this is not a science blog but you can read it up on Grokipedia.

Doubly labeled water has been used to measure energy expenditure in different populations and let’s just say, the findings have been very surprising.

Who do you think burns more calories (after adjusting for body weight and composition) – a hunter gatherer or a couch potato?

- A hunter gatherer who walks 15,000 steps a day and spends his days hunting and foraging

- A modern person in an industrial society who needs a week to get the same exercise a hunter gatherer gets in a day

Well, guess what?

As it turns out, they both burn roughly the same amount of calories each day.

Multiple studies have confirmed this to be the case:

- Hadza hunter gatherers have roughly the same total daily energy expenditure as sedentary westerners (view here)

- Female farmers in western Africa used the same amount of energy daily when adjusted for fat-free body mass as women in Chicago (article here and paper here)

And yes, this is after accounting for body size and composition.

Shocking!

You are a product of millions of years of evolution, not “intelligent design”

The reason why the additive energy expenditure model seems very intuitive to people is because they are used to dealing with machines.

Of course if you left your phone on but didn’t use it all day, it will burn battery slowly and any activity you did on the phone would burn additional battery on top of it.

Makes complete sense right?

As it turns out, the human body has some mechanisms to regulate energy expenditure that adapt to your activity levels over time.

We are not simple mechanical machines like the additive energy expenditure model assumes.

Adding exercise burns extra energy in the short run, but your body adapts to it over the weeks and your total energy expenditure returns to within some range (the rate and extent of adaptation is genetic).

The body really tries its best to match your energy expenditure with your energy intake when expenditure is higher than intake (the reverse also happens but to a much much lower extent because too much food was pretty much never an evolutionary pressure).

- The body tries to increase energy intake by making you hungrier (hormonal changes like increased ghrelin, lower leptin)

- The body cuts down on energy expenditure where it can (eg. you move around less, your libido goes down, your immune system is less active, your thyroid hormones go down making every cell work slower, etc.)

The modern equivalent would be something like your smartphone adapting to your usage patterns by decreasing maximum screen brightness, turning off processor cores, and lowering screen refresh rate for a while if you overuse your phone for a few days. Your body is “adaptive technology”.

These adaptations predate humanity. We got it all “for free”.

We evolved over millions and millions of years of food scarcity. And not just us, but also all the species that came before us (our ape ancestors) and parallelly with us (other animals like mice, tigers, lions, etc).

Metabolic adaptations are coordinated by the hypothalamus of the brain. The hypothalamus evolved far before any modern vertebrate animal species and has been preserved ever since. It is a major control center for:

- Hunger/satiety (via leptin, ghrelin, insulin signals, etc.)

- Energy expenditure and thermogenesis

- Hormonal axes (thyroid, adrenal, reproductive)

In other words, these adaptive evolutions are extremely ancient and present in almost all vertebrate species (even fish have a hypothalamus).

The first creatures that were evolving hypothalamuses were not intelligent like modern humans and did not solve problems like modern humans (eg. they weren’t storing food for later use).

If they did not manage to acquire enough energy (whatever their food source was) and they kept burning the same amount of energy, they would die.

Over time, evolution “taught” these species to adjust their metabolism to the energy they had available to them.

If they had access to less energy (prolonged deficit), functions would be cut back and they would burn less energy. This allowed them to survive the periods of food scarcity.

If they had access to more energy (prolonged surplus), they would burn more energy over time (slightly as upward flexibility is very limited because too much food was not an evolutionary pressure) and then store the surplus energy (even animals without a clear hypothalamus store energy as fat/glycogen).

As it turns out these adaptations are so useful that they have been preserved in all species that have a hypothalamus (i.e. vertebrates like fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals), which includes us humans.

Many parts of our brain are very ancient and evolved under ancient evolutionary pressures that predate our species by a very long time. We have inherited all these useful adaptations thanks to our ancestral species, and them thanks to theirs.

The Constrained Energy Expenditure Model

All of this has been formalized as a new model called The Constrained Energy Expenditure Model.

Under this model, as physical activity increases, the body adapts by cutting down caloric expenditure elsewhere to try to keep the total energy expenditure within some acceptable range.

The human body adapts in various ways:

- You move around and fidget less so you “waste” less energy

- Hunger goes up to get you to eat more whenever you do get access to food (increased ghrelin, lower leptin)

- Sex hormones drop not just to save energy but also because a prolonged period of food shortage is not a good time to have a baby (for men their testosterone drops and interest in sex declines, for women their cycles become irregular and can stop completely)

- The body becomes more efficient at digestion and movement (there is less wastage)

- Thyroid hormones drop to make every cell in the body slow down and thus conserve energy

- The immune system slows down

- The body becomes more efficient in many ways (e.g. the mitochondria might have lower proton leak, so fewer calories are wasted as heat)

- etc.

The adaptation happens over weeks and months so initially you see extra calorie burn from added exercise, but it keeps reducing and then eventually plateaus.

I know all of this makes it sound like exercise is not that great for you, but as I will cover in the next post in this series, the constrained energy expenditure model actually shows that exercise is even more beneficial than previously thought (it just isn’t by itself the key to long term sustainable fat loss).

This model is not perfect but is closer to reality

This model explains what coaches and athletes had noticed for a long time and what they called “metabolic damage”.

In reality it is not “damage”, but a beneficial adaptation that evolved to keep you alive during periods of food scarcity.

It also explains to some extent the classic signs of overreaching/overtraining:

- Drop in performance, decreased alertness, strength plateaus

- No mood to do anything other than lay around

- Constant fatigue and feelings of exhaustion

- Bad recovery (soreness lasts longer)

- Low libido / no interest in sex

- Irritability

I will say that this model is very cutting edge (much of the research is only 10-15 years old) and I’m certain we will learn more as more research takes place.

We are much closer to truth now than we were with the old additive model. I will discuss the implications of it all in the next post because I don’t want to make this one too long.

You can’t adapt down to zero

Some of you might have the question “What about people who burn a lot of calories like Michael Phelps or triathletes”. They are burning thousands of calories every day in physical activity alone (so are pregnant women).

Under this model, their basal energy expenditure would have to go below zero to adapt to all the activity, right?

Their body does adapt to their extreme amounts of physical activity, but the body can only adapt so much. There is a point beyond which it cannot cut down things anymore and then it seems we are back at operating with the additive model.

In a study where total energy expenditure was tracked for athletes running a transcontinental race (they were running 250km a week for 20 weeks, so almost a marathon every day), they learned that the athlete’s bodies adapted and “saved” 600 calories a day from their pre-race levels (20% of their TDEE).

After that adaptation is hit, how much energy they can expend comes down to how much energy they can intake.

At their elite extreme endurance events, athletes push themselves to perform well despite metabolic adaptations. The thing that physically holds these extreme athletes back is their ability to eat and digest food.

Most people’s ability to digest food plateaus at ~2.5 times their basal metabolic rate (BMR) over the long run [Note how cutting edge all this research is – this study is from October, 2025]. Some athletes have digestive systems that can absorb ~3 times their BMR. But still not unlimited.

A part of what makes Michael Phelps such an amazing athlete is that he’s at the 3 times his BMR heuristic (although his actual diet is nowhere close to the 12,000 calories meme). All elite endurance athletes are limited by their ability to eat a lot and absorb more energy.

But I won’t get into it any more than I already have because extreme athletes (which include pregnant women) are not the intended audience for this series.

In the next piece I’m going to talk about the implications of constrained energy expenditure and how you can use it to maximize your health goals (or at least avoid spinning your wheels and wasting time).

– Harsh Strongman

Update: There is a newer paper that claims that physical activity is directly associated with total energy expenditure without evidence of constraint or compensation. However, this study is not relevant because:

- There are no timelines mentioned (it takes weeks for adaption to happen)

- There is no caloric deficit. There is a nice cop out: “Energy balance was a key piece of the study… We looked at folks who were adequately fueled. It could be that apparent compensation under extreme conditions may reflect under-fueling.”

| Title |

|---|

![Traits Women Find Attractive Traits Women Find Attractive (And How to Score Yourself) [PART 1: Physical Aspects]](https://lifemathmoney.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Traits-Women-Find-Attractive-1.jpg)